“I’m just one disabled girl, sitting in front of a church, asking them to love us.” - Amy Kenny

Growing up as a pastor’s kid feels like trying to go about your day in a house with glass walls. You have very little privacy, and everyone feels entitled to an opinion about how you live your life. The music you like, the clothes you wear, the books you like are all up for public commentary. In this environment, it shouldn’t have surprised me to learn that the parents of other teens in the church had been making passive aggressive comments about how much I missed church because of chronic pain. But at the time, I still had so much hope that this type of behavior was the exception, not the rule.

Years later, a woman actually came up to me and told me that several people hadn’t believed I was actually sick, and that they thought my food allergies were made up. I plastered on a vague expression, smiling and nodding while internally enraged. In high school, I spent most days curled up in a ball on the couch wishing I could swallow ice cubes to calm my enflamed digestive system. But that sort devastating pain wasn’t enough for these people? I walked away feeling as if someone had just shredded the few happy memories I’d been able to piece together from my chronically ill adolescence.

Even as an adult in other congregations, women stage whispered while I was still in the room, talking about me as if I wasn’t right there. I was a nuisance, high maintenance, someone who didn’t make enough of an effort to get to church. In every case, I felt like no one saw the intense effort I made to try to make it to services, the mornings getting ready only to curl up in tears, unable to move. I’d celebrated most of my major life events—weddings, funerals, baby dedications—with these congregations. But in the end, the community that I believed cared about me (both my body and soul) ultimately only wanted to support me as long as I possessed an able-body they could use.

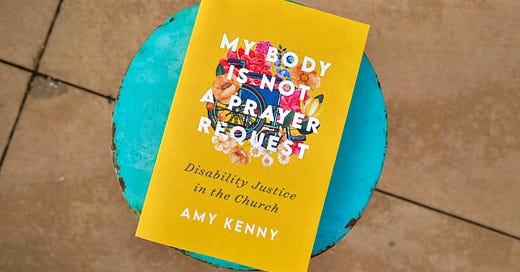

In the beginning of My Body Is Not a Prayer Request, Amy Kenny says, “The most harmful ableism I’ve experienced has been inside the church” (26). When I read those lines and had to stop. This was the first time that I’d ever seen the quiet part said out loud. Many of the people in these churches are ableist.

Some churches focus on curing their disabled members, telling them that if only they had enough faith, they’d be free of their disability. But Kenny describes how so many churches focus on prayer for cures for their disabled members instead of fully embracing them as they are:

“Instead of trying to desperately cure disabilities, the church should do the slow and difficult work of healing the surrounding society by tearing down spaces, practices, and mindsets that are inaccessible to disabled people, even when those spaces are inside the church itself.” (14)

When people emphasize that disabled people will have “perfect” bodies in heaven, that deflects from caring for disabled bodies RIGHT NOW. To Kenny, a key point in her theology is that God made us ALL in His image, so disabled people should be embraced and loved just like anyone else. We too are the image bearers of God:

“If we really believe the good news and that we claim to cherish, we would find ourselves advocating for disability justice as part of our role as fellow image-bearers. Disabled people bear God’s image. Not despite our bodies or once we receive our ‘new-creation bodies.’ Right now.” (61)

Again and again, Kenny returns this idea, noting how many forms of ableism come from people believing that her disabled body reflected a flawed faith. In every chapter, she drives home point that problem is in their flawed theology and ableist mindset, not disabled bodies.

All disabled people are different, and we often disagree about the language we use. In Chapter 5, Kenny explains that she believes that her disability is a blessing, a gift that has brought her closer in her relationship with God. Using that language is a very personal decision, and for me, I would never use the words “gift” or “blessing” in regards to my disability. And if someone came up to me and told me that my disability was a blessing from God, I would be deeply offended. If another disabled person chooses to use this language about their disability, to reclaim the word and ideas for their own sense of self, that’s their right, and I respect that. But enough disabled people don’t hold that perspective that I don’t think it’s appropriate to tell new-to-disability-studies readers that, in general, it’s okay to refer to people’s disabilities as blessings or gifts. This is another example of why it’s always vital to ask every disabled person what language they prefer to use in regards to their disability.

At the end of each chapter, Kenny walks readers through disability 101, explaining concepts like Crip Time, Spoons, the social model of disability, and the importance of using the correct language around disability. She then applies those ideas to faith and church culture, illustrating that ableism is just as big of a problem in the church as it is outside of it. At the end of many of the chapters, Kenny gives resources for further reading from disabled BIPOC and/or LGBTQ+ writers, so it’s obvious from the outset that My Body Is Not a Prayer Request shouldn’t be the end of someone’s education around disability. It’s only the beginning.

Around the Web

“Ancients & Ambrosia: Read Appalachia: An Interview with Kendra Winchester, founder of Read Appalachia” (The Devil’s Cut)

I did a Q&A with Lemon, author of Done Dirt Cheap, for her substack, The Devil’s Cut. It includes all things Appalachian Lit, Corgis, and jello salads.

Things I Made Recently

Read Appalachia

The Pride Month episode of Read Appalachia is live! I interviewed Willie Edward Taylor Carver Jr., the author of Gay Poems for Red States, and Zane McNeill, the editor of the anthology Y’all Means All.

Behind the Mic (AudioFile Magazine)

I’ve recorded SO MANY episodes for Behind the Mic, recommending audiobooks like The Great Reclamation, Quietly Hostile, and The Late Americans. Subscribe to never miss one of my audiobook recs!

Book Riot

Read or Dead

Last fall, I became the new co-host for Book Riot’s Read or Dead podcast. It’s about all things thrillers and mysteries. I’ve recorded several episodes now, and I’ve enjoyed exploring this genre.

Newsletters

I write two newsletters for Book Riot: True Story, and Read This Book. You can subscribe to them here.

Can I comment here? Anyway, Hi Kendra. Happy almost 2024. I have not read this book, BUT I am a born again Christian and I must say, as a people group, we suck. We really do. I think it's because we don't read, as a group. Ignorance abounds in the church. I'm trying to not be the kind of person you describe in your book review here. I guess all I can say is that I'm sorry for the life time of BS you've endured from the church.